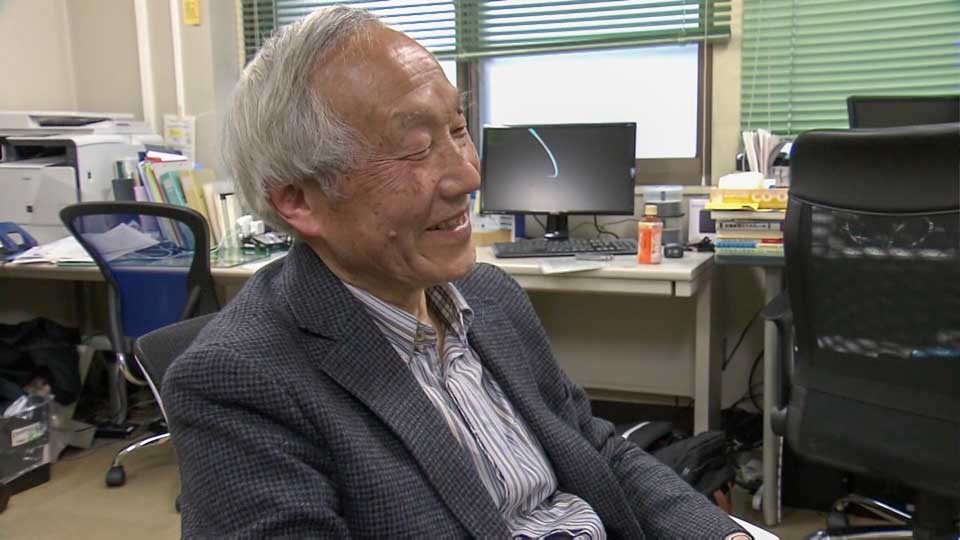

Engineer Uemura Masayuki had an outsized impact on the lives of countless children around the world. In the mid-1980s, he created a video game console for Nintendo that was known in Japan as the Famicom and elsewhere as the NES. It enjoyed enormous success, selling 60 million units and putting Super Mario, Zelda and Dragon Quest into homes everywhere. In the wake of Uemura’s death in December at the age of 78, NHK’s Kagawa Nao recalls a conversation he had with the gaming industry icon about his work and the nature of play.

In the spring of 2019, I sat down with Uemura Masayuki to talk about what it means to “play”. Some of his answers surprised me, and others resonated deeply a year later when the COVID-19 pandemic transformed the way people interacted socially.

Ready, player one

Uemura explained to me that the Famicom’s success was the result of a confluence of factors, including improvements in computer processing power, the rise of gaming media, and changes in the ways children were brought up.

“I think the Famicom games were a way to play at home when urbanization made it more difficult to play outside,” he said.

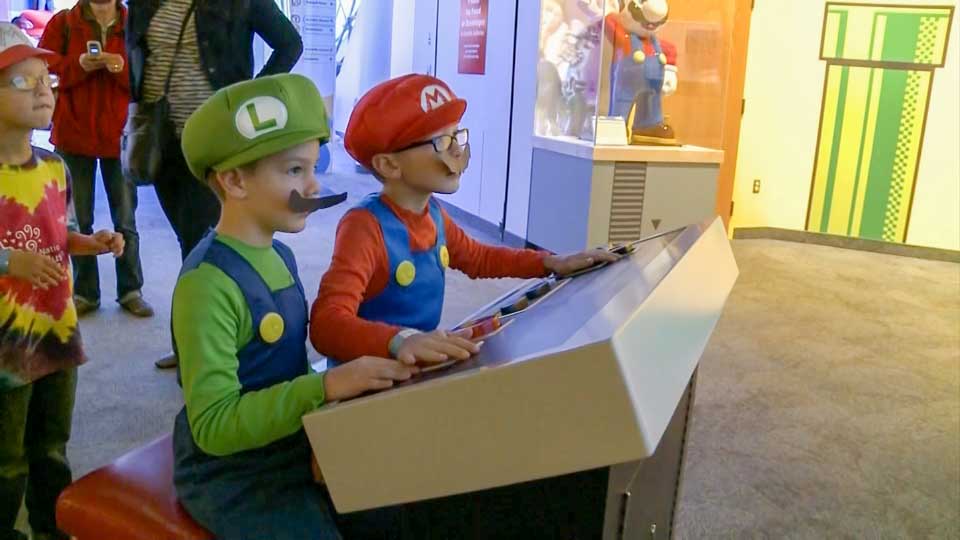

Children took to the new type of game console with relish, but parents and teachers worried about them missing opportunities to socialize. Uemura told me he saw no such problem.

“When people criticize video games, they often portray it as a lonely activity with players sitting by themselves, staring at a TV,” he said. “The reality seems to be the opposite. People watch the same screen, take turns, share information. I think the games are actually a social adhesive that connect people.”

Global success

Uemura explained that it was the Japanese knack for creating cute characters that helped make the NES a hit overseas, and he attributed that knack to the animism that has influenced Japanese culture for centuries.

“The concept says objects have lives of their own,” he said. “And it manifests in gaming as simple, peaceful titles that contrast with the violent games from abroad. Pac-Man is really just playing tag, and Pokemon is catching insects. Anyone in the world can understand how to play that.”

Uemura retired from Nintendo in 2004 but remained involved in the industry at Ritsumeikan University’s game research center, where he served as director for 10 years.

I asked him if gaming had anywhere left to go, having already embraced the internet and virtual reality. His answer surprised me.

“We still haven’t created a video game that’s better than menko,” he said, referring to the traditional Japanese card game in which players throw their cards onto a hard floor, aiming to flip their opponents’ cards.

“In terms of graphics, we have attained the highest point we can possibly reach,” he said. “But we can’t reproduce that physical feeling of hitting something.”

In fact, Uemura thought that graphics had possibly become too good, so that they no longer left enough to the imagination. He felt that was why the old graphics of his first famous console had enjoyed a revival.

“People prefer it when they can use their imagination,” he told me. “What your eyes see isn’t realistic, but it’s real in your head. The more room for imagination, the more fun it is.”

Future of gaming

We talked about what made games fun, and whether it was possible to create one that never got dull.

“Impossible,” he said with a smile. “The only thing that people will never get sick of is people.”

Our interview took place before the coronavirus pandemic. But I was reminded of it when that started and it became more difficult to interact with people, and Nintendo’s latest “Animal Crossing” game became a huge hit.

Over the past two years, games have continued to evolve, and on top of that, services catering to individual users have increased and become more satisfying.

But for the first time, I have truly come to understand what Uemura talked about when he said that ultimately, we never get bored with people.

Be the first to comment